What then was the statue Heraclides describes?

The appearance of Scopas' name in the testimonia has led scholars to approach the image of Apollo Smintheus from a Greek point of view. But Chryse did not lie within a wholly Greek orbit: it was in Anatolia, where we may expect to find a complex series of quite different cultural associations. Smintheus himself betrays by his name a non-Greek element, the element -nth- being a well-known characteristic of a non-Hellenic linguistic stratum. (15) Ancient opinion on the meaning of the epithet was divided, some commentators deriving it from the name of the town of "Sminthus" or "Sminthe" (Hesychius, s.v. Σμινθεύς, σμίνθος, ed. Schmidt), others from the Mysian word σμίνθος (mus). (16) The appearance of the name in Homer gave entrée to the Greek world, but the Anatolian background of the cult, going back perhaps to the Early Bronze Age, deserves consideration. (17)

A symbolon is far more than a simple insigne. In the human world, a symbolon is a proof of identity, often with legal status (LSJ, s.v.). In the divine realm it also has special significance. The close association of Smintheus and his mus is the key to understanding his cult and iconography. For it is the Near Eastern tradition that establishes the paramount connection between gods and their animals, so prominent in Greek practice.

The Near Eastern tradition of showing animals as companions of the gods stretches back at least to Protodynastic times, when beasts are depicted as physical supports for their divine masters. (18) In Arkadian art, gods frequently appear on their animal "vehicles". (19) The convention is widespread in the ancient Near East. The motif found special favor in Syria and Anatolia. One need think only of the several divinities arriving on their animals at the assembly of Hittite gods in the rock sanctuary of Yazilikaya. (20)

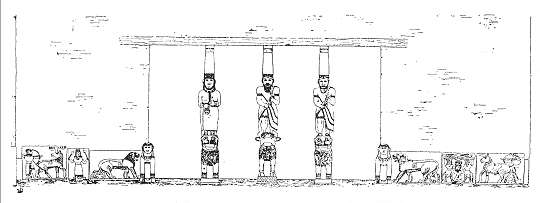

The most striking expression of the close and practical relationship between god and beast is surely found in the sculptures of the portico of Kapara's palace at Tell Halaf, ancient Guzana, of the later ninth century B.C. (Figure 2). (21) These magnificant basalt figures, now tragically destroyed, but unforgettable in their impact, nobly embody the majesty of the gods and their symbolic animal companions. Although the majority of such Late Hittite figures come from southeastern Anatolia and Syria, (22) the same formal connection between god and animal can be found even among the distant Urartians, who produced the comparable seventh-century figures from Toprakkale. (23)

This Near Eastern background is vital to the understanding of the iconography of Smintheus. The various aetiological stories repeated by Strabo were devised to account for a cult and an iconography whose affinities lay far outside Greek tradition. (24)

Let us now turn to the statue mentioned by Heraclides. Heraclides speaks of a xoanon. While Strabo, as is well known, broadens the definition of this word to include statues of many kinds, there can be no doubt that Heraclides uses it to mean an ancient wooden statue. (25) We must therefore think of a definitely early, probably a quite primitive, type.

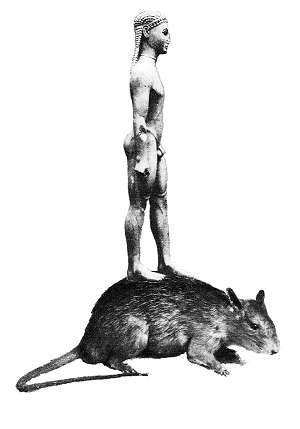

Heraclides says that this xoanon κατασκευασθῆναι ἐπὶ τῷ μυί This is not the same as saying that the mus lies beneath the foot of the statue, but must refer to a completely different placement of the symbolon.

Heraclides refers to mues. All previous scholars have assumed that "mice" are meant, (26) but they have not been sufficiently objective or strongminded on this point. In the Batrachomyomachia - surely the unassailable authority for this question - mus may mean either "mouse" or "rat" (Bat. 173 and passim). Heraclides is a native of Pontus, and Aristotle (HA 600 b 13, 632 b 9) uses the term Ποντικὸς μῦς for a rodent far larger than a mouse. The memory of the plague-carriers imported along with more welcome Euxine wheat is preserved in the modern Greek word ποντίκι, which, with or without the modifying μέγα, refers to rats. There can be little doubt that Heraclides describes a sanctuary swarming with rats. Only one conclusion can follow.

The old conception of the statue must be abandoned. The reconstruction I propose in Figure 3 accounts for the full range of evidence presented above. In all details it fits both the literary testimony and what is known of the background and affinities of the Smintheus cult. The statue by Scopas, the statue pictured on the coins of Hellenistic and Roman times, is but a pale recollection of the early xoanon. It is now clear why the symbolon, the mus, remained in the memory of all who saw it. To imagine the effect of the image on the viewer, we may borrow the words of Dio Chrysostom: (27) "And among men, whoever might be burdened with pain in his soul . . . even that man, I believe, standing before this image, would forget all the terrible and harsh things which one must suffer in human life."